2026…

I’m thrilled to announce that I’ve been selected to sit on the Editorial Board for The Journal of Beatles Studies, published by Liverpool University Press.

The Journal of Beatles Studies, co‐edited by Holly Tessler (University of Liverpool) and Paul Long (Monash University) and published biannually in association with the University of Liverpool, is the first open‐access academic journal devoted to rigorous, peer‐reviewed research on The Beatles.

Launched in September 2022, it features original essays, notes, and reviews that interrogate and expand Beatles scholarship across disciplines – historical, musicological, cultural, economic and beyond. Its aims are to foster emerging research in new contexts and communities, challenge prevailing narratives, and assess The Beatles’ enduring cultural and economic impact.

It’s a true honour to be on the Editorial Board for such an important publication, helping to position The Beatles as a prism for broader historical, social, and cultural enquiry.

Before All You Need Is Love, there was The Word. Tucked within Rubber Soul, this largely ignored track marks a turning point for The Beatles – a moment when love became more than just romance. It became a mantra, a message, and a mission. The Word foreshadows the band’s later idealism while encapsulating the creative restlessness that defined their mid-’60s evolution. Exploring the song’s meaning reveals why it deserves more recognition in The Beatles’ catalogue.

On 3 December 1965, The Beatles released Rubber Soul, an album that marked a major turning point in their career, and the moment they got serious, or at least as serious as four millionaires on a steady diet of weed could get. Out went the love songs, in came strange, introspective songs about jealousy, detachment, domestic boredom, and in the case of The Word, a kind of love far bigger than boy-meets-girl.

John Lennon later said of the song: “It sort of dawned on me that love was the answer, when I was younger, on the Rubber Soul album. My first expression of it was a song called The Word. It seems like the underlying theme to the universe.”

Lennon’s phrasing is telling: “It dawned on me.” Like a sudden flash of light. And The Word sounds like that too – a wide-eyed declaration, a chorus of voices repeating its new-found wisdom, as though trying to convince both the world and itself.

In retrospect, The Word is where The Beatles started to see their own influence. This wasn’t just another love song, it was The Truth, and they were the ones delivering it. The idea would grow with Lennon in particular: from Rain (“I can show you” / “Can you hear me?“) to Revolution (“You tell me it’s the institution, Well, you know, you’d better free your mind instead”), to Imagine (“I hope someday you’ll join us, and the world will live as one”), and not to mention his ‘70s radicalism. But here, in late 1965, it’s still playful.

According to Paul McCartney, The Word is the only Beatles song to have been written while under the influence: “We smoked a bit of pot, then we wrote out a multicoloured lyric sheet, the first time we’d ever done that. We normally didn’t smoke when we were working. It got in the way of songwriting because it would just cloud your mind up. It’s better to be straight. But we did this multicoloured thing.”

Later, Paul described how Yoko Ono came to his flat asking for manuscripts to give to John Cage. She was given The Word lyric sheet replete with psychedelic Lennon/McCartney doodles.

A mantra-like structure, an almost religious fixation on a single word, this was something different. It was The Beatles experimenting not just with music, but with message. Love, as a subject, had been there from the start, but never like this.

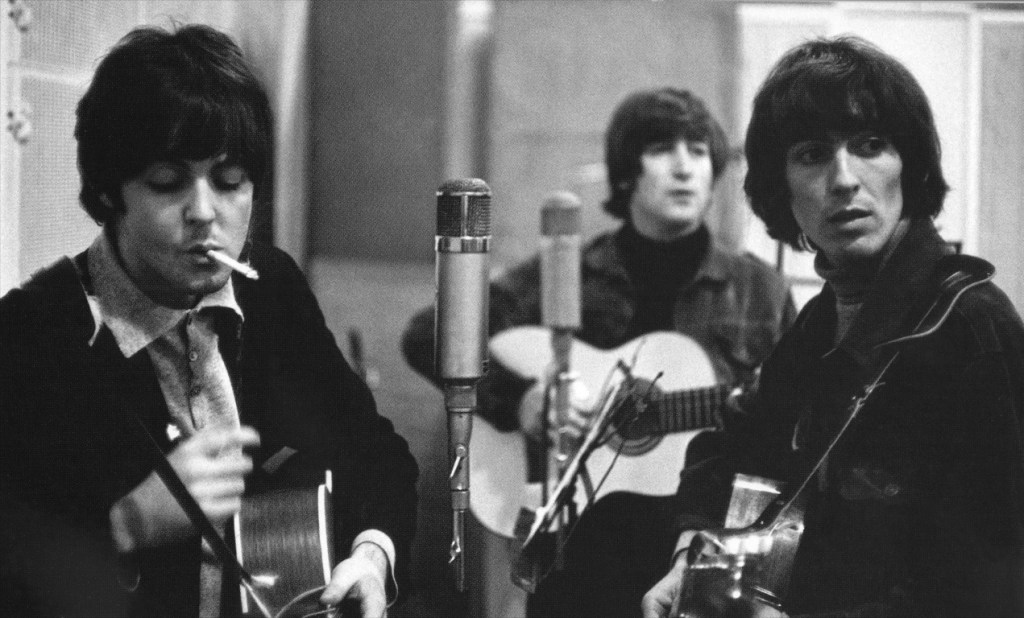

Photo: Leslie Bryce

In the studio

Recorded on the night of 10 November 1965, The Word came together quickly. Just three takes for the rhythm track, then overdubs: harmony vocals, Paul on piano, and George Martin adding a harmonium.

It’s a song built around a drone-like simplicity. In fact John and Paul originally conceived it around a single note, a technique that would come to define their later experiments. That repetition, the pre-Hendrix guitar stab, that hypnotic quality, it all makes The Word feel less like a pop song and more like a chant. Or, perhaps, a doctrine. From hereon in The Beatles would take these themes ever further, push them into new shapes. But this is the precise moment where the shift begins, where love stops being a line in a song and starts being The Word.

John had conflicting views on Christianity. It could be said that his ultimate conclusion was crystal clear in 1970’s God from John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band. Nevertheless, in 1977 he briefly became a born again Christian after years of bingeing on a diet of tv evangelists (Whatever Gets You Thru The Night was a direct quote by Reverend Ike). Typically, this was another passing fad and by 1979 John was mocking Bob Dylan’s conversion to Christianity by composing Serve Yourself in direct response to Gotta Serve Somebody.

In 1963 John wasn’t sure what to believe and theology appeared to have been troubling him for years. In Love Me Do – The Beatles’ Progress author Michael Braun asked his opinion on nuclear war (the Cuban missile crisis still being a hot topic). John replied: “I don’t suppose I think much about the future. I don’t really give a damn. Though now we’ve made it, it would be a pity to get bombed. It’s selfish but I don’t care too much about humanity – I’m an escapist. Everybody’s always drumming on about the future but I’m not letting it interfere with my laughs if you see what I mean. Perhaps I worried more when I was working it out about God.”

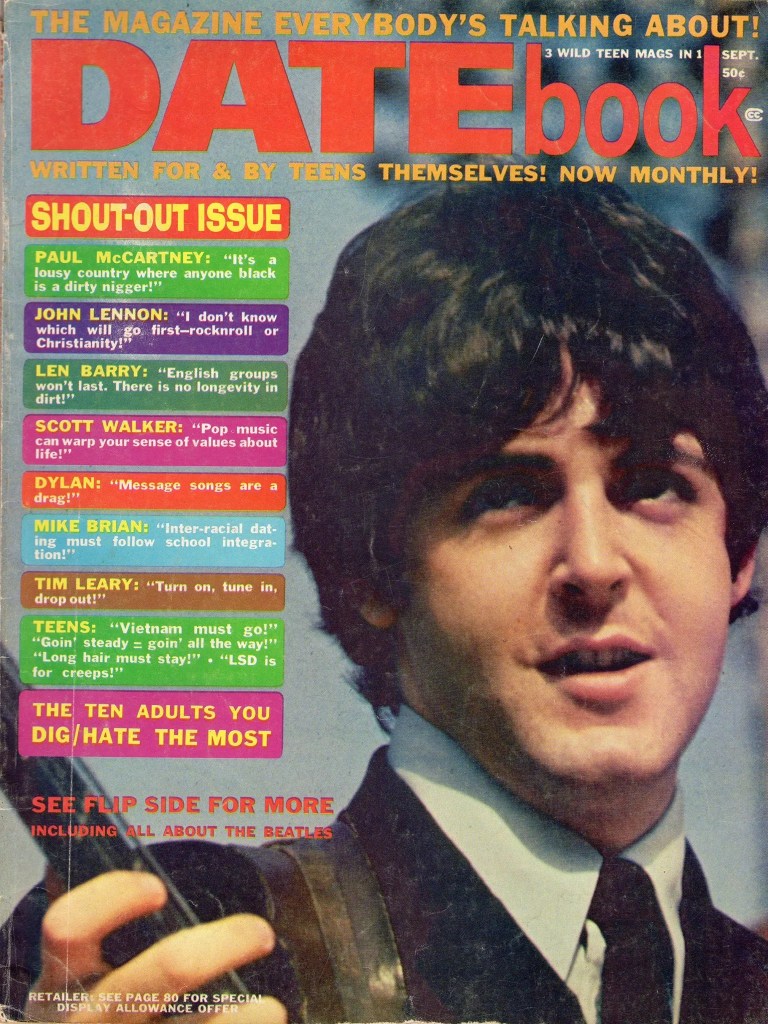

John’s notorious interview with Maureen Cleave, originally published in the 4 March 1966 edition of The London Evening Standard (and later repurposed for US magazine Datebook) is now infamous for the quote that prompted the precursor to the summer of love – the summer of burning piles of Beatles records. But hidden away in the article is a telling line: “He (John) paused over objects he still fancies; a huge altar crucifix of a Roman Catholic nature with IHS on it; a pair of crutches, a present from George; an enormous Bible he bought in Chester; his gorilla suit.” Ignoring the giant baboon ensemble for a moment, John’s ‘enormous Bible’ was, I believe, undoubtedly the source for many of the themes and lyrics of The Word.

On the surface, The Word is a straightforward call to universal love. John, who at this point was just a few months away from the lysergic revelations of Tomorrow Never Knows sounds like he’s stumbled onto something enormous and wants to shout it from the rooftops. “Now that I know what I feel must be right,” he exclaims, “I’m here to show everybody the light.”

But the choice of phrase “the Word” carries baggage. In Christian theology, it’s a weighty term. And, if a stoned John Lennon decided to grab his Bible for lyrical inspiration, then three guesses as to where he’d immediately be drawn?

John and Paul and John and Paul

The Gospel writer’s John was the mystic of the disciples, declaring the divine power of love. His Jesus is a figure of cosmic importance, the living manifestation of God’s plan for humanity. Lennon, while always curious, was never a great respecter of religious institutions. He came at it from a different angle: love as a human force and/or choice.

The Bible promises salvation through Christ; Rubber Soul suggests enlightenment through universal, psychedelic, or maybe just good old-fashioned free love. John’s subsequent gurus, Timothy Leary, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Magic Alex, Allen Klein, Arthur Janov et al, all let him down. Undeterred, by 1973’s Mind Games he still maintained that love was the answer. And he knew that for sure.

There’s an almost evangelical fervour to The Word. It’s insistent, commanding: “Say the word and you’ll be free.” Lennon sings like a man who’s found revelation, desperate to drag the rest of us into the light. And though he’d later dismiss this period as “fat-Elvis” there’s something compelling in his wide-eyed belief.

It’s easy to see Lennon and McCartney’s dynamic reflected in the New Testament’s two biggest heavyweights: John, the dreamer, the poet, the man with a hotline to the ineffable; Paul, the pragmatist, the doer, the man who took the message and actually made something of it. The Apostle Paul took Christianity beyond its origins, turning it into a movement. McCartney, in his own way, did something similar taking Lennon’s raw emotion and shaping it into commercial songs.

In the end, The Beatles and the Bible both offer “the Word” as a path to truth. The difference is in the direction they point: the Gospel towards God, Lennon and McCartney towards John.

The Jesus of John’s Gospel says, “I am the way, the truth, and the life.” Lennon would later counter with: “All You Need is Love.” The theological debate continues, but watching the 1967 Our World performance it’s hard to ignore the comparison between the disciples sitting at the feet of Jesus and Mick Jagger sitting at the feet of The Beatles.

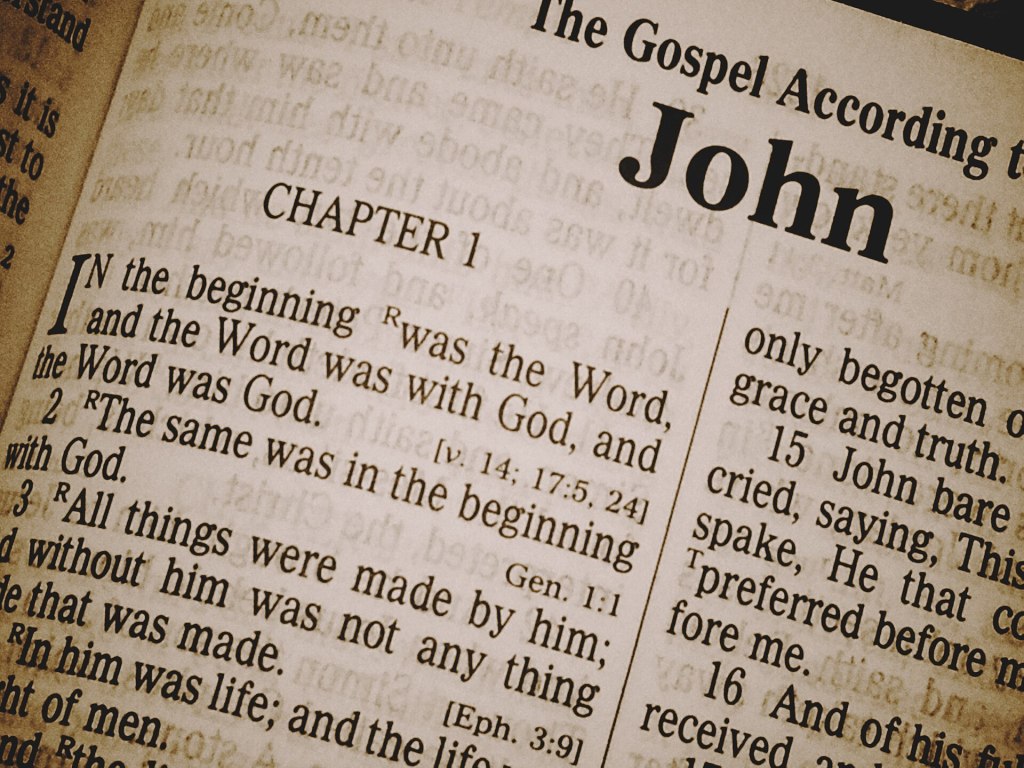

The Word in scripture

The Bible doesn’t mess around when it comes to defining the Word. It opens the Gospel of John with the kind of statement that doesn’t leave much room for ambiguity: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

In other words, the Word (“Logos” in Greek) isn’t just a message, an idea, or a nice thought about love. It’s Jesus. A living, breathing manifestation of divine truth. And when John later says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), he’s making it clear: this isn’t philosophy, this is a person. God’s truth, walking, preaching, healing, and ultimately being sacrificed to save the world.

For the early Christians, this idea of the Word was huge. The Apostle Paul – Christianity’s greatest PR officer – spent much of his life hammering the point home.

He wrote: “For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God.” (1 Corinthians 1:18)

To the Apostles Paul and John, the Word was transformative. It was salvation. It was the truth.

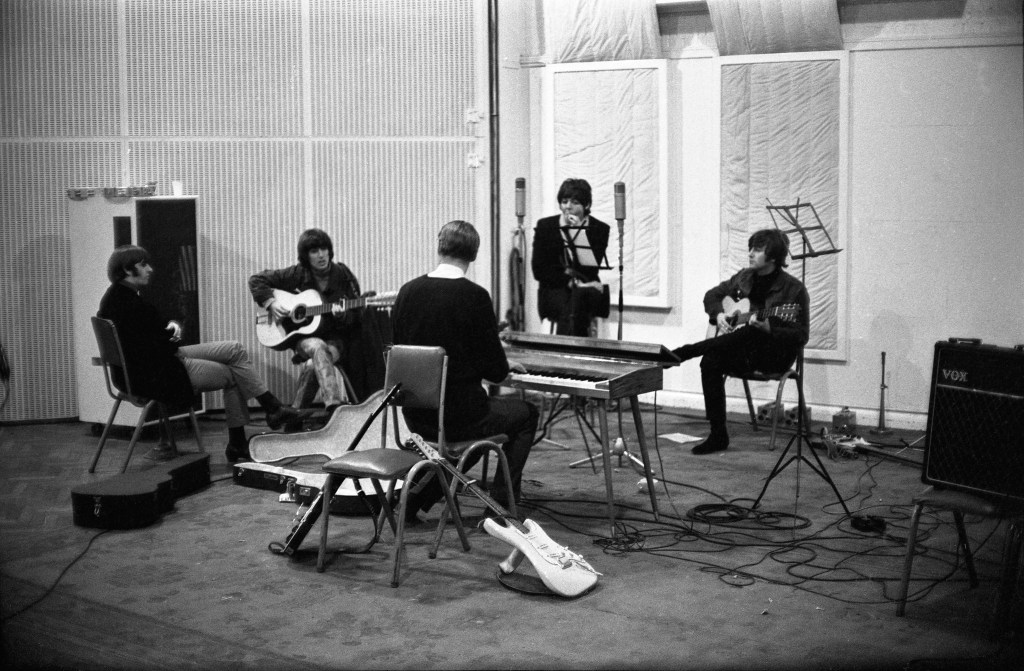

Photo: Leslie Bryce

The Word in The Beatles

Then, nearly 2000 years later, John and Paul sat down to write a song called The Word and came up with… well, something a bit different.

“In the beginning I misunderstood, but now I’ve got it, the word is good.“

If that phrasing sounds familiar, it should. The Beatles’ generation had grown up in a country where scripture was everywhere, and just as they used newspaper articles and tv shows for inspiration, they borrowed the cadence of religious revelation from The Bible.

But the answer to the eternal question that The Beatles land on? Love. The same love that Jesus commanded, but stripped of divinity and, whether they realised it or not, they tapped into something ancient. A belief in the Word as a truth so big, so universal, that it could change everything.

And if you’re looking for eternal salvation? Well, that depends on which version of the Word you believe.

“In the beginning I misunderstood, but now I’ve got it, the word is good.”

Biblical parallel:

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” (John 1:1)

Connection:

That opening phrase: “In the beginning” isn’t just some throwaway line. It’s straight from the Gospel of John (and, before that, Genesis). In the Bible, “the Word” is divine: Jesus Christ, the eternal truth, the living embodiment of God’s will. But The Beatles swap Jesus for love, reshaping a deeply theological concept into something secular and universal. It’s less the Word made flesh and more the Word made largely ignored album track.

“Say the word and you’ll be free, say the word and be like me.”

Biblical parallel:

“Then you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” (John 8:32)

“Whoever claims to live in him must live as Jesus did.” (1 John 2:6)

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations…” (Matthew 28:19)

Connection:

Freedom, enlightenment, transformation – it’s all here. In John’s Gospel, Jesus describes truth as the key to liberation. In The Word, love takes on the same role: say it, believe in it, and you’ll be free. The second line: “be like me” hints at another biblical echo. John’s first epistle teaches that to truly follow Christ, you live as He lived. But here, Lennon isn’t pointing to Jesus, he’s pointing to himself.

“Be like me” shifts the focus away from discipleship and toward something more self-prophetic.

If The Word has a biblical counterpart, it’s The Great Commission – the moment when Jesus sends his followers out into the world to spread (what else?) the Word. Lennon has slipped into the role of an evangelist. He’s not just singing a love song; he’s preaching a gospel. And just like Jesus calling his disciples to follow him, Lennon urges the listener to “be like me” – to embrace “The Word” and to spread it.

John the Beatle as John the Baptist? It’s not as far-fetched as it might seem. He’s heralding a new truth, preparing the way – not for Christ, but for capital-L secular Love.

“It’s so fine, it’s sunshine…”

Biblical parallel: “Then the righteous will shine like the sun in the kingdom of their Father.” (Matthew 13:43)

Connection:

Light. Radiance. Enlightenment. In both The Word and the Gospel of Matthew, those who receive the message don’t just understand – they shine. This is more than just happiness; it’s illumination. A spiritual transformation. Love, in Lennon’s world, is a force of revelation.

“Now that I know what I feel must be right, I’m here to show everybody the light.”

“It’s the word I’m thinking of, and the only word is love”.

Biblical parallel:

“I am the light of the world. Whoever follows me will never walk in darkness, but will have the light of life.” (John 8:12)

“You are the light of the world. A town built on a hill cannot be hidden.” (Matthew 5:14)

“In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (John 1:4-5)

Connection:

Light, in the Bible, is truth, wisdom, salvation. Jesus calls Himself the Light of the world, and later, He passes that mantle to His followers. Lennon brazenly steps into that role, positioning himself as an enlightened figure bringing the light to the rest of us. Again, the biblical weight remains, but the meaning shifts: divine revelation is replaced with self-discovery, and salvation with love.

“Say the word and you’ll be free”

Biblical parallel: “It is for freedom that Christ has set us free. Stand firm, then, and do not let yourselves be burdened again by a yoke of slavery.” (Galatians 5:1)

Connection:

Lennon’s message isn’t just about love – it’s about freedom. And in Galatians, Paul says exactly the same thing: the Word (that is, Christ) is the key to true liberation. Both The Word and the Bible present their message as a means of breaking chains, casting off burdens, transcending the limitations of the past.

“Say the word and be like me”

Biblical parallel: “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched – this we proclaim concerning the Word of life.” (1 John 1:1)

Connection:

There’s something strikingly Christ-like in Lennon’s phrasing here. To say the word is to transform, to become like the messenger. The early followers of Jesus spoke of the Word of life as something tangible, something they had seen and touched. Lennon echoes this – his Word isn’t abstract. It’s real. It’s something to be proclaimed.

“Give the word a chance to say that the word is just the way.”

Biblical parallel:

“I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.” (John 14:6)

Connection:

Jesus makes it clear: He is the way. The Beatles keep the phrasing but swap out the subject – love, not Christ, is the ultimate path. It’s a radical departure. Lennon’s version of love isn’t built on worship, but it does promise a kind of transcendence.

“Everywhere I go I hear it said, in the good and the bad books that I have read.”

Biblical parallel:

“Do not believe every spirit, but test the spirits to see whether they are from God.” (1 John 4:1)

“For everything that was written in the past was written to teach us.” (Romans 15:4)

Connection:

Lennon’s reference to good books and bad books suggests a broad search for truth – sacred texts, philosophy, maybe even a bit of countercultural wisdom. The Bible itself warns against false teachings, urging believers to discern what is truly from God. Paul, on the other hand, assures that all scripture exists to teach humanity. The Beatles offer a different conclusion: love is the only truth that matters, the only thing worth taking from secular books.

Photo: Mike McCartney

From whispered sweet nothings to whispered wisdom

There was a time – simpler, more innocent – when the usage of “word” or “words” in a Beatles song meant little more than whispered promises in a lover’s ear. Back in 1963 Lennon and McCartney were still playing by the old Tin Pan Alley/Tamla Motown rules, where language in pop was there to serve romance, nothing more.

At this stage, words weren’t weighty. They weren’t there to enlighten, to free, or to guide the listener toward anything deeper. They were just soft syllables of desire – spoken, whispered, and sung to a girl in the back row of the Liverpool Locarno Ballroom. In P.S. I Love You (1962), the “few words” being treasured weren’t profound – they were just another way of saying I miss you, darling.

And then, once The Word was released in 1965, from this moment onwards, everything changed.

Photo: Leslie Bryce

No longer whispered in an ear, the Word was now shouted from the rooftops. It was good. It was the way. It was everything. And what was the Word? Love, of course – but not the kind that needed moonlit walks or stolen kisses. This was L-O-V-E.

The Word was their first real mission statement and “words” in Beatles songs were never the same again.

Getting Better (1967)

“Me used to be angry young man, Me hiding me head in the sand, You gave me the word, I finally heard, I’m doing the best that I can.”

In Getting Better, the Word becomes personal – an epiphany, a revelation. Someone has given the singer “the Word” and now he’s a changed man. If The Word was about spreading enlightenment, Getting Better is about receiving it. A sequel of sorts, a follow-on. “The Word” wasn’t just spoken anymore – it was heard, understood and lived. Having realised The Word is love, the singer, while not exactly 100% committed, is at least “doing the best that I can.“

Across the Universe (1968)

“Words are flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup…“

Lennon, by this point, is drowning in words – untethered and infinite. These aren’t words whispered into his lover’s ear; they’re words escaping from his own mind, floating out into the ether. If the word means love then it makes even more sense: “Love is flowing out like endless rain into a paper cup.” It’s been a life changing journey since P.S. I Love You.

Let It Be (1969)

“Speaking words of wisdom, let it be,” “Whisper words of wisdom, let it be.“

Again, we’re back to whispered words – but this time, they aren’t about love or longing. They’re words of wisdom, divine in nature, echoed like a prayer. Where The Word made love into gospel, Let It Be delivers something even closer to scripture.

George: Words as a weapon

If Lennon and McCartney evolved words into something sacred, George Harrison often took a different approach: using them to bite, to jab, or to complain. His relationship with words was not one of enlightenment but frustration.

Think for Yourself (1965)

“I’ve got a word or two, to say about the things that you do.“

Not exactly love is the answer. George’s words are a warning and a rebuke. He isn’t spreading enlightenment; he’s the school teacher angrily parping: “Detention!” at Charlie Brown.

Only a Northern Song (1967)

“It doesn’t really matter what chords I play, what words I say, or time of day it is…“

By this point, poor old George is exhausted. Words have lost their meaning entirely, reduced to industry fodder, just part of the machine. “The Word” was supposed to be all-powerful – but here, words don’t even matter anymore.

The Word became scripture (The Word).

The Word became action (Getting Better).

The Word became wisdom (Let It Be).

The Word became snarky (Only a Northern Song).

The Word became flesh and vinyl

As everyone knows, The Beatles changed so much between 1963 and 1969, but one of the subtlest, most telling evolutions was in their use of words. By the end, The Beatles had taken words to their highest and lowest points – sacred and hollow, cosmic and exhausted. But it all started in 1965, when they stopped whispering and started preaching.

Lennon and McCartney weren’t quite at All You Need Is Love levels of proselytising just yet, but the groundwork was being laid. The language of scripture, stripped of its religious binding, was already shaping their message. By the time Sgt. Pepper and Magical Mystery Tour rolled around, the transformation would be complete: from rock band to secular prophets, preaching something undeniably spiritual, yet detached from its religious origins. Nevertheless, the echoes of scripture are everywhere.

I love this song, in fact it’s quite possibly my favourite Beatles song. I was delighted to discover that it’s also Johnny Marr’s favourite Beatles song. So, if nothing else, I am more than happy to have something – but especially this – in common with Johnny Marr.

Chris Shaw March 2025

Hosted by The Big Beatles and 60s Sort Out podcast, a behind the scenes recording at the recent live episode of Chris Shaw’s final ‘I Am The EggPod’ podcast, featuring interviews by Rob Manuel with EggPod fans and alumni, including:

Mark Lewisohn, Samira Ahmed, Joel Morris, Nadia Shireen, Jason Hazeley, Julia Raeside, Matt Everitt, Kevin Eldon, Jill Connolly, Mark Newlove, Eleanor Gray, Adam S Leslie, Chris Chibnall, James Marshall… and Chris’ wife!

Search for The Big Beatles and 60s Sort Out wherever you get your podcasts.

To support the upkeep of I am the EggPod, or to send a donation to Chris – and to hear the full 2 hour version (as well as lots of exclusive EggPod content) go to https://patreon.com/eggpod

Recorded at Opera Holland Park in London, Samira Ahmed, Mark Lewisohn and David Janson discuss the 60th anniversary of The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night premiere, with Chris Shaw. “The world is still spinning and so are we and so are you. When the spinning stops – that’ll be the time to worry. Not before. Until then, The Beatles are alive and well and the Beat goes on, the Beat goes on.”

Recorded at Opera Holland Park in London, Stuart Maconie, David Quantick and Laurence Rickard discuss the 60th anniversary of The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night premiere, with Chris Shaw. Plus special guests Alex Lowe, Rob Manuel and Kevin Eldon.

Saturday 6th July 2pm – 4:30pm

Opera Holland Park Ilchester Place London W8 6LU

On 6th July 2024 EggPod LIVE returns to Opera Holland Park, London to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the A Hard Day’s Night premiere!

Beatles fans, mark your calendars for Saturday 6th July 2024 as EggPod LIVE returns to Opera Holland Park, London – for the Last EggPod of All – to celebrate the milestone 60th anniversary of the premiere of ‘A Hard Day’s Night‘ (6th July 1964). Join us for another afternoon of Beatles magic and nostalgia.

More guests to be announced, but at this year’s show, the special guests are…

Mark Lewisohn

The world’s leading Beatles historian and author of Tune In, The Beatles Recording Sessions, The Complete Beatles Chronicle and many more. Mark will share his incredible insight into behind-the-scenes stories and a journey through the making of this historic Beatles film and its beloved soundtrack album.

Samira Ahmed

EggPod favourite, returns to EggPod LIVE for 2024. Last year Samira was instrumental in unearthing a previously unheard recording of The Beatles at Stowe School from 4 April 1963 – the earliest known UK live concert audio. A Hard Day’s Night is Samira’s favourite Beatles album and movie – and her enthusiasm and knowledge of this period is deliciously infectious!

Laurence Rickard

Actor, writer and comedian best known for Ghosts, Horrible Histories, Yonderland and We are Not Alone, joins the EggPodders to share his love for A Hard Day’s Night. Laurence is a huge Beatles fan and recently appeared on I am the EggPod talking about The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper outtakes.

Stuart Maconie

Stuart is a legendary radio DJ and TV presenter, writer, journalist, and critic working in the field of pop music and popular culture. He is a presenter on BBC Radio 6 Music where, alongside Mark Radcliffe, he hosts its weekend breakfast show.

David Quantick

Novelist, comedy writer and critic, David has worked as a journalist and screenwriter. A former freelance writer for NME, his writing credits have included On the Hour, Blue Jam and TV Burp. He won an Emmy Award for Veep in 2015.

PLUS! Special guest – David Janson

David Janson appeared in A Hard Day’s Night as the young boy joining Ringo for his walk. David will be sharing his memories of filming those scences.

Don’t miss your chance to meet other Beatles fans, as well as the guests —save the date for Saturday 6th July 2024 and join us for a Fab afternoon of A Hard Day’s Night fun! Starts at 2pm.

Tickets are available here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/eggpod-live-2024-tickets-879546947597

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

13 JUNE, 2024

Podcaster Eleanor Gray and Beatles author Vikki Reilly discuss the first in The Beatles’ Anthology series of albums with Chris Shaw.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

MAY 26, 2024

Guitar legend Earl Slick discusses the 1980 recording sessions for Double Fantasy / Milk and Honey. With Chris Shaw.

Since 2018 it’s been pure joy interviewing Beatles fans about their favourite albums, movies and moments.

Along the way, I feel like a real community has grown and new friendships have been made. A number of listeners have said that I am the EggPod has helped them during tough times, as well as introducing them to new Beatles and solo Beatle albums. Well, what could be better!

Since EggPod started, dozens of new Beatles podcasts have been launched and I hope that this show in some way helped encourage others to spread the word to new generations about this incredible band, with their story soaked in history, joy and impossible chunks of serendipity.

I hate outstaying welcomes, and would rather end this particular story on a high. It’s been a tough decision but I think it’s the right one.

So now is the time to ‘do a rooftop Mal’ and pull the plug on EggPod.

The last EggPod of all will be live at Opera Holland Park, London on 6 July 2024. It will be the perfect opportunity to close the curtains on this most joyful chapter of my life – and I hope it’s brought you some happiness too! And what better way to do it than with a roomful of friends?

If you’d like to come and say goodbye – and see some super special guests for the final episode, then you’ll be more than welcome!

Tickets are here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/eggpod-live-2024-tickets-879546947597

I’d like to say thank you on behalf of the pod and I hope I passed the audition

Chris x

#EggPodLive2024

Emergency EggPod online!

A review of the special screening of Let It Be in London on 7th May 2024 – with comments from Stuart Maconie, Matt Everitt, John Simm, Sanjeev Bhaskar, Guy Pratt and Eddie Izzard.

On 6th July 2024 EggPod LIVE returns to Opera Holland Park, London to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the A Hard Day’s Night premiere!

Beatles fans, mark your calendars for Saturday 6th July 2024 as EggPod LIVE returns to Opera Holland Park, London to celebrate the milestone 60th anniversary of the premiere of ‘A Hard Day’s Night‘ (6th July 1964). Join us for another afternoon of Beatles magic and nostalgia.

Guests to be announced, but returning to the event will be special guest Mark Lewisohn who will share his incredible insight into behind-the-scenes stories and a journey through the making of this historic Beatles film and its beloved soundtrack album.

Stay tuned for future guest announcements!

Don’t miss your chance to meet other Beatles fans, as well as the guests —save the date for Saturday 6th July 2024 and join us for a Fab afternoon of A Hard Day’s Night fun!

Tickets are available here: https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/eggpod-live-2024-tickets-879546947597

Songwriter and producer Owen Parker discusses The Beatles’ 2006 remix/mashup album – and Circue du Soleil soundtrack – Love. Hosted by Chris Shaw.